Teladoc Health

A multinational telemedicine company — the first and largest virtual healthcare company in the United States — providing on-demand, remote medical care through telephone and videoconferencing software, mobile apps, analytics, and licensable platform services.

Founded in 2002 in Dallas, Texas, Teladoc pioneered virtual healthcare with a system that enabled member patients to consult remotely at any time with state-licensed doctors. The company launched nationwide in 2005, and by 2007, boasted close to 1 million members. Several large employers — including AT&T — offered the service to their employees as a health benefit.

Over the next decade, virtual healthcare proved to be a far more cost-efficient way for employers to deliver higher-value medical care to end-users. Teladoc Health grew exponentially, both in supply — acquiring its two main competitors at the time — and demand — the Affordable Care Act propelled many of the largest insurance companies to sign with Teladoc.

They went public in 2015 — the only telemedicine company listed on the NYSE — and used that momentum to further build their market depth and breadth, expanding service capability — behavioral health, dermatology, sexual health — and delivery systems — acquiring a consumer-facing mobile app, and developing customizable software platforms for on-site medical practices and hospitals.

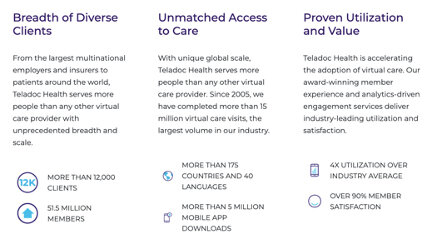

Teladoc Health now operates in more than 175 countries, serving nearly 52 million members — numbers that continue to grow as they augment their preeminence in the virtual healthcare industry with concurrent acquisition and development strategies.

Strategic Challenge

A growth-driven company anchoring a still-emerging and rapidly changing industry, offering a broad, fluid portfolio of acquired and internally developed products and services in both B2B and consumer-facing channels creates complex brand challenges.

Companies, products, and services absorbed through acquisition bring with them their own built-up brand equities and end-user awareness. Does it best serve the acquiring company to retain those existing brand names? Is it worth considering a re-branding effort to assimilate them under a master brand? Or is co-branding an effective alternative?

Products and services added to the overall portfolio through in-house development start, like any new offering, with a blank slate. Typically, a naming strategy for B2B leans more toward the functional, descriptive end of the spectrum, while consumer-facing offerings are often better served with more evocative, emotionally engaging monikers. Is brand synergy maximized with one consistent naming approach across all segments? Or is end-user awareness of the master brand even a relevant consideration in long-term corporate strategy?

Managing the push-and-pull of flexibility versus consistency in volatile times can be filed under “building the plane while you’re flying it.” How can you plan ahead when industry upheaval and expansion is likely to continue into the foreseeable future? How do you avoid spinning your wheels, continuously reinventing the wheel — asking the same set of questions over and over each time?

Nomenclature System

The term nomenclature refers to the devising or choosing of names for things. In branding, a nomenclature system establishes, in advance, a rule structure to strategically guide all future brand-naming decisions.

Developing a nomenclature system requires strategic foresight — thinking forward, holding space for any conceivable new product and/or service category, and for any line extension, sub-brand, or division. The objective is to holistically envision and analyze the complete portfolio of offerings. It is a 10,000-foot view that will guide and streamline organization-wide decision making on the ground whenever a naming requirement arises.

A nomenclature system doesn’t provide actual brand names, only the decision rules and criteria to inform any future naming initiative. Like: if or when to retain or modify the existing brand name of an acquired offering. Or: when and how to integrate/annotate “outsider” brands under the master-brand identity or insignia. And: what is the format and tone for language when targeting various key audiences. Having rules in place solidifies the first few tiers of a naming brief, saving time and therefore money.

Examples of Nomenclature Systems: Apple, Inc.

Brands are represented both linguistically — the type and tone of words — and graphically — typeface, color, and any additional design elements. Apple — a consistent leader in category creation — employs a strong visual system to support their descriptive, modern product- and line-extension names. Their nomenclature system simplifies complex new concepts, giving consumers an easy way in, an easy analog/metaphor to wrap their heads around. It also gives Apple credibility when “redefining” existing product categories — Apple TV, Apple Watch, Apple Music.

Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia

From her humble, home-keeping roots, Martha Stewart has expanded into a powerful lifestyle brand represented in print, broadcast, product development, and licensing.

Despite the breadth and variety of the empire’s multiple holdings, there is a consistent presentation across all offerings — the brand name Martha Stewart is followed by a simple, wholesome, descriptive product or category name.

Unlike Apple, this brand isn’t re-defining or inventing new product categories, but rather curating lifestyle choices from a particular sensibility. This sensibility is reflected across all offerings — a friendly, welcoming appeal established by a general consistency in tone and color palette. Without being as rigorous and structured graphically as Apple, the brand is present in every execution, easily recognizable to consumers by the strength of the name alone.

A system need not be rigid and confining to be effective.

Levi Strauss & Co

Among the Levi Strauss & Co. holdings are multiple distinct brands. Most — but not all — include some version of the word Levi. Each of the brands caters to a different audience, and each is uniquely branded and marketed specifically to those target audiences. A nomenclature system that allows for different architecture for different brands or sub-brands offers flexibility and distinction — a value-conscious consumer is able to enjoy the halo of the Levi’s brand without diluting the premium reputation of the core brand.

In closing,

A nomenclature system should be designed to work for your brand, your brand’s architecture, your brand’s present and future footprint. It cannot anticipate every possible eventuality, but it will provide a framework for decision making in the majority of cases. The intention is to frame a system both powerful enough to create meaning, yet ambient enough to scale.

How conspicuously a brand structure is imprinted, how connected offerings are to each other and back to the master brand, can be considered on a continuum from not-so-much [Levi’s] to dominantly so [Apple], with plenty of room for variation in between.